Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a common condition affecting around one in seven people assigned female at birth in Australia. It is associated with pelvic pain, inflammation and scarring, and in some cases can affect fertility.

Many people with pelvic pain have endometriosis, or have had endometriosis diagnosed in the past. Importantly, the severity of endometriosis does not reliably match the severity of pain. Some people may have extensive endometriosis with little or no pain, while others may experience significant pain despite only mild disease.

What is endometriosis?

The lining of the uterus is called the endometrium. It is the tissue that grows inside the uterus each month and bleeds away with a period. When tissue like the endometrium is found in other areas around the pelvis (not just inside the uterus), it is called endometriosis. The areas of endometriosis are called lesions.

-

Endometriosis lesions can form a spotty covering on the sidewalls of the pelvis or on the surface of pelvic organs. More severe endometriosis may:

Grow into pelvic organs, and/or

Form round cysts in the ovaries called endometriomas (often called “chocolate cysts”).

Most endometriosis lesions can’t be seen on an ultrasound scan. Endometriosis is a pain you can sometimes see at a laparoscopy, but it is often only one part of pelvic pain. Many girls and women with endometriosis have a mix of symptoms, not just period pain. It is important to remember that there are many types of pain you can’t see.

-

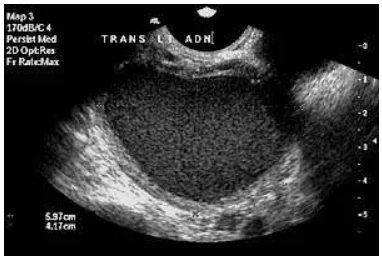

Women with more severe endometriosis may have an endometrioma. These are also called chocolate cysts.

An endometrioma:

Grows inside the ovary, which can make the ovary larger

Has a thick wall

Often contains thick brown fluid (old blood)

On ultrasound, an endometrioma can have a more even, grainy appearance. At laparoscopy, opening an endometrioma can allow the brown fluid to come out, and the cyst wall may be seen inside the ovary and removed.

-

Symptoms vary widely and can include:

An aching, sharp or burning pain in the pelvis, tailbone (coccyx), bottom, pubic area, rectum or lower back

Pelvic pain outside of periods

Bowel symptoms: a sense of incomplete emptying, pain opening bowels, inability to pass wind or anal pain, food intolerances, bloating, diarrhoea, or constipation

Bladder symptoms: needing to go to the toilet frequently, urgency, slow passage of urine, or bladder pain

Hip, groin or abdominal pain

Low energy, behavioural or emotional changes, anxiety or depression

Heavy periods can contribute to iron deficiency anaemia, which can make you tired

-

Many women with endometriosis also have irritable bowel–type symptoms. While a few have endometriosis lesions in the bowel wall, most don’t. Their bowel can look normal but doesn’t always behave normally. There are also many people with irritable bowel symptoms who have never had endometriosis.

-

Yes — absolutely. It’s common for symptoms to start in the teen years, sometimes from the very first period. This may be more likely if there is a family history of endometriosis or severe period pain. It’s important not to delay seeking help. Early support can improve quality of life, reduce suffering, and (for some people) may help protect future fertility.

-

Chronic pelvic pain is often poorly understood and not always recognised because it may not show on scans or at an operation. People with pelvic pain can have a wide range of symptoms for different reasons.

Pain may start in a pelvic organ such as the uterus, uterine tubes (fallopian tubes), ovaries, endometriosis lesions, bladder, or bowels. Pelvic pain may also start in muscles or joints following an injury. Sometimes pelvic pain begins during a period of severe stress without a clear precipitating event. Other times, no single cause is found.

-

elvic pain is often considered “chronic” if it is present on most days for at least 3–6 months.

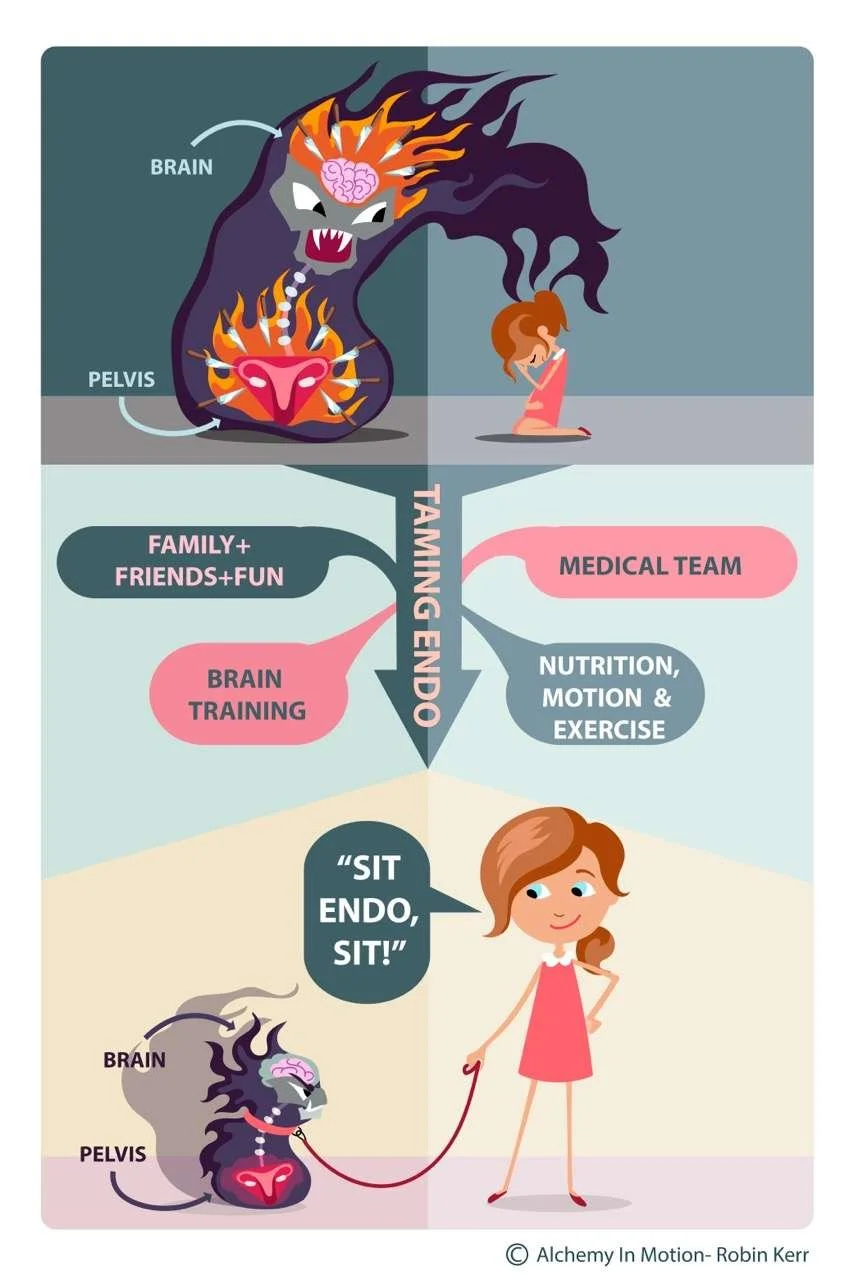

Once pain has become persistent, the situation is usually more complicated:

Even when the original trigger settles, the body can keep interpreting the area as threatened and keep producing pain.

Pelvic muscles may tighten to protect the body, leading to painful tight muscles and spasms (this can feel like a cramp inside the pelvis).

Nerve pathways that send pain messages to the brain can become sensitised (sometimes even light touch can feel very painful).

Stress and anxiety can sensitise these pathways further.

Pain can affect sleep, school/work, mood and confidence, which can create a vicious cycle.

Once muscles and nerves start behaving abnormally, other organs can develop problems too. Pelvic floor muscles work best when they can tighten and relax normally. They help control bladder and bowel motions. Trying to urinate or open your bowels through painful, tight pelvic muscles that can’t relax normally can be extremely painful.

How is endometriosis diagnosed?

Transvaginal Ultrasound

Endometriosis has previously required a surgical procedure for the diagnosis to be confirmed. Emerging evidence suggests that a greater number of cases can be diagnosed with increasing accuracy using non-invasive techniques such as transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis should be offered a transvaginal pelvic ultrasound as the first-line investigation. A pelvic MRI can be offered if ultrasound is not available, or if deep endometriosis is suspected. If transvaginal ultrasound is not possible or not appropriate, due to age or sexual history, and MRI is not available, a transabdominal ultrasound could be suggested. Surgery is not required as a first-line option to diagnose endometriosis. Specialist ultrasound scans and pelvic MRIs should be performed and/or interpreted by a healthcare professional with specialist expertise in gynaecological imaging.

For young people with significant period pain ultrasound should be used to assess causes including endometriosis. Your specialist may use transabdominal ultrasound when transvaginal ultrasound is not suitable. MRI or transperineal ultrasound also may be considered by a specialist experienced in these modalities.

Recent advancements in blood and saliva tests for endometriosis show promise for non-invasive diagnosis, with several studies indicating potential for accurate detection through biomarkers. These methods are not widely accessible in Australia, however, we look forward to their utilisation over the coming years.

Laparoscopy (keyhole surgery)

A laparoscopy is an operation where a doctor puts a telescope through a small cut in your umbilicus (belly button) to look inside your pelvis. They can then:

Diagnose if any endometriosis is present, and

Remove endometriosis as completely as possible (when appropriate)

There are different types of surgery:

Excision: lesions are cut out

Cauterisation/diathermy (ablation): lesions are burnt

Some laparoscopies are relatively short and straightforward, while others take longer and are more complex. It depends on where the endometriosis is and how extensive it is. Endometriosis in teens can look different to endometriosis in older adults and can be easier to miss. In older people it is often a darker brown colour. In young people, it may look like tiny clear blisters or subtle areas that can be hard to see. It’s also important to remember the amount of endometriosis found at laparoscopy doesn’t reliably match the amount of pain. Many people with endometriosis also have other pain problems (for example: bladder pain, irritable bowel symptoms, headaches, pelvic muscle pain, vulval pain, or pain on most days). Even if endometriosis is present, a lot of period pain may also come from the uterus, even if the uterus looks normal.

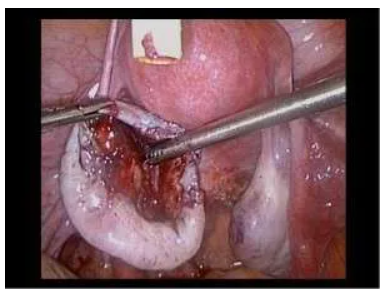

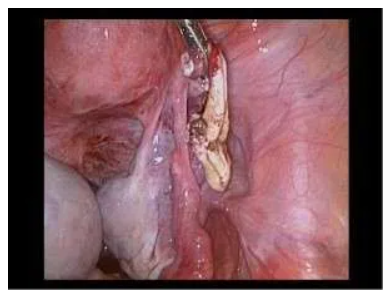

The following photos were taken at the laparoscopy of a woman with an endometrioma inside both her ovaries. They show what an endometrioma looks like on ultrasound:

the brown fluid that comes out when the ovary is opened. The brown fluid gives an endometrioma an even grainy appearance on ultrasound.

the cyst wall inside the ovary, and,

the cyst wall after it has been removed

At a laparoscopy, opening the endometrioma in the right ovary allows the brown fluid to come out. In the final photo, the endometrioma in the left ovary has had the brown fluid removed. Now the wall of the cyst needs to be removed from the ovary.

Treatment and symptom management (endometriosis-focused)

Once pain becomes persistent, it is unlikely that any one treatment will make it go away completely. However, you can feel optimistic about the future. There are many ways to manage pain and make it a much smaller part of your life.

A helpful plan often includes a combination of:

1) Medicines for pain relief (with professional advice)

Taking an anti-inflammatory (NSAID) either instead of paracetamol or in combination with it is sometimes recommended.

Some NSAIDs work by blocking prostaglandins and can work best when taken early, before pain gets severe (tracking helps).

Stronger pain relievers (including codeine) are only available on prescription and should only be used with medical advice.

2) Hormonal treatment (often first-line for symptoms)

The contraceptive pill is often used as a first-line treatment to regulate periods and reduce symptoms. There are many types of pills, and some are better suited to help with endometriosis-related symptoms than others.

Taking the pill continuously decreases the number of periods per year and can reduce symptoms. However, prescribing pills “back-to-back” may not be wise in some situations if there is no diagnosis or no follow-up plan. The pill is not suitable for everyone for many reasons (age, culture, health, choice, side effects).

3) Laparoscopy + uterine pain management (combined approach)

Pelvic pain is often multifactorial; a combined approach can be helpful. Even when endometriosis is present, a significant part of period-related pain can still come from the uterus itself (uterine cramping and sensitivity), even if the uterus looks normal on scans or at surgery.

A combined plan may include:

Laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) to confirm whether endometriosis is present and, where appropriate, remove visible endometriosis lesions (for example by excision).

Hormonal treatment to reduce bleeding and uterine cramping and to help keep symptoms controlled after surgery. This may include:

Staying on the pill and taking it continuously to reduce or stop bleeds, and/or

Using a hormonal IUD (such as Mirena®), sometimes inserted at the time of laparoscopy, to make periods lighter and less painful.

This combined approach aims to:

Treat endometriosis lesions (where surgery is appropriate), and

Reduce the “monthly trigger” of bleeding and uterine cramps that can keep pain cycles going.

Important notes

It can take a few months for hormonal treatments (including a hormonal IUD) to settle, and irregular bleeding or cramping can occur early on.

Hormonal treatment choices should be personalised (age, health conditions, preferences, side effects, and whether contraception is needed).

Surgery is not the right choice for everyone. If repeat surgeries are being considered, discuss the potential for adhesions (scar tissue) and how that may affect future operations.

If pain continues despite these approaches, it does not mean nothing can be done. Ongoing pain may be driven by pelvic muscles, bladder or bowel sensitivity, or sensitised nerves—so additional supports (pelvic health physiotherapy and a persistent pain plan) may be an important part of recovery.

The Australian Living Guidelines for Endometriosis have more information about Australia’s Standards for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis. Go to The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) website here.