Management of a Patient with Chronic Pelvic Pain

Once pain is persistent, a reduction in pain together with improved function and wellbeing may be more achievable goals than cure. Even so, substantial improvement is achievable with the right team of health professionals. Start with simple analgesia such as paracetamol ad nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Dysmenorrhoea

Dysmenorrhoea is often only one component of CPP. If endometriosis, dysmenorrhoea, or cyclical aggravations of pain are present, the aim to management is to minimise the number of periods or the amount of bleeding by creating a progestogenic (decidualised) environment. Amenorrhoea is optimal, but may require a combination of treatments (eg levonorgestrel IUCD and continuous OCP, or levonorgestrel IUCD and oral dienogest).

Management includes:

A monophasic oral contraceptive pill (OCP)

Oral progestogen (dienogest 2 mg or norethisterone 5 mg) or levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD)

The etonorgestrel implant may be effective if amenorrhoea can be achieved

For severe cases, dienogest 2 mg daily continuously has been shown to be non-inferior to GnRH agonists, has fewer hypoestrogenic side effects and improved quality of life. 11

Hysterectomy treats dysmenorrhoea well when fertility is no longer an issue. However, a hysterectomy should not be considered as a cure for CPP, as it is possible pain can persist despite the hysterectomy due to the pre-existing muscle tightness, central sensitization and psychological distress.

Bladder symptoms

These symptoms may be due to a range of conditions; however, painful bladder syndrome is common.12 ‘Flares’ resemble urinary tract infections, but urine cultures are negative despite haematuria.

Management includes:

Assessing and excluding potential diet triggers, particularly acidic foods/drinks (citrus fruits, fizzy drinks, caffeine, cranberries, artificial sweeteners, tomatoes) drinking 1.5–2 L fluid daily (mostly water) in normal weather.

Acute management of flares (ie drinking 500 mL water mixed with 1 teaspoon bicarbonate of soda or two urine alkalinising sachets, then 250 mL water every 20 minutes for a few hours); antibiotics should be avoided unless infection is proven; providing a request form for urine culture if symptoms flare provides security that urine infection will not be missed.

Use of medications including amitriptyline, oxybutinin, solifenacin and others, as outlined by Lau et al, 13 (amitriptyline has the added advantage of helping with sleep, headaches, the persistent pain condition, pelvic muscle pains and some irritable bowel symptoms, and is a good first choice).

Vulvovaginal irritation

Management depends on the conditions present and includes:

Avoiding soap/perfumed body wash – replace with QV/Cetaphil or Dermaveen body wash, and water only on vulval area

Exclusion of candidiasis – where repeated episodes of candidiasis have been proven, fluconazole 200 mg every 72 hours for three doses then weekly for 6 months as a private prescription is effective 14

Low-dose amitriptyline, this can be compounded as a topical agent

Vulval dermatological review

Topical oestrogen if patient is post-menopausal

Pelvic physiotherapy.

Pudendal neuralgia

Pudendal neuralgia causes a burning or sharp pain in the ‘saddle’ area, anywhere from the clitoris back to the anal area, when sitting. It may be uni- or bilateral and may be associated with increased clitoral arousal.17

Management includes:

Avoiding activities that compress the nerve, such as cycling, crossing legs

Using a ‘U-shaped’ foam cushion with the front and centre area cut out when sitting

Pelvic physiotherapy to down train pelvic muscles and reduce pressure on pudendal nerve

Ceasing straining with bowels or bladder

Neuropathic medications.

Managing pelvic muscle pain

Diagnosing the pain correctly may avoid unnecessary treatments and procedures.

Management options include:

Avoiding aggravating activities (e.g. core strengthening exercise, prolonged positions)

Stretches

Yoga and mindfulness

Vaginal dilators

Pelvic physiotherapy to ‘down-train’ muscles

Optimising bladder and bowel function

Botulinum toxin injection for severe cases, which requires a referral to Gynaecologist 18

Managing central sensitisation

Management includes:

an explanation that the nerve pathways have physically changed and become sensitised

exercise – ‘the best non-drug treatment for pain’ (eg walking; where inactive, start with time outside each day, then a short daily walk with pacing to avoid over-tiredness)

optimisation of sleep patterns 19

pain psychology

neuropathic medications such as low dose amitriptyline, a serotonin-noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitor (SNRI) such as duloxetine, or an anticonvulsant such as pregabalin; in women, use small doses and increase slowly to a low peak dose (eg amitriptyline 5 mg 1–3 hours before bed, slowly increasing to 5–75 mg). 20

Gillett and Jones 20 provide a comprehensive and highly recommended discussion of medicines useful in women with pelvic pain. Initially, it is advisable to explain that each of these medications’ suits about half of those who take it, and that more than one type may need to be trialled, or a combination of two medications taken.

Managing the psychosocial sequelae of PPP

It is important to ensure the patient knows the GP believes in her pain and will take her concerns seriously. Although becoming overtired is not helpful, giving up work rarely improves pain. It is best to keep active and keep moving.

Re-engaging with family, friends and community through activities with high motivational value for her will encourage mobilisation. This might include volunteering at a school if she enjoys being with children, study in an area that interests her, or craft activities she has always enjoyed. Exercise and meaningful activities help make pain a smaller part of her life.

A pain psychologist can consider life factors contributing to the overall pain experience. This includes a history of sexual assault, if present. Although the majority of women with pelvic pain have not been sexually assaulted, where this is present recovery is more complex.

Investigations

There is a limited role of laboratory testing and imaging in diagnosing patients with PPP, history and physical examination are the most important components. Although these diagnostic tests may be required for referrals to Gynaecology and/or Urology.

A complete blood count, C-reactive Protein, urinalysis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing, prostate specific antigen test, and pregnancy test may be done to screen for chronic infectious or inflammatory processes and to exclude prostate cancer and pregnancy.

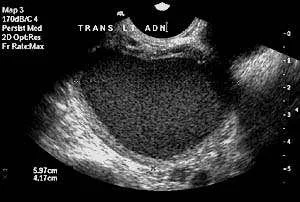

Pelvic ultrasonography is helpful to identify pelvic masses, adenomyosis, hydrosalpinx, and ovarian cysts. Ectopic endometrial glands such as ovarian endometriomas, peritoneal implants and deep pelvic endometriosis may be visible on ultrasonography. Magnetic resonance imaging may be useful to define an abnormality found on ultrasonography.

Unfortunately, all these investigations may return normal and sometimes even laparoscopy, leaving many patients without a diagnosis for the cause of the persistent pelvic pain.